Telepathy

by Marinus Jan Marijs

Telepathy (tele, far, and pathein, to experience) is a term introduced by F.W.H. Myers in 1882 to denote “the ability of one mind to impress or to be impressed by another mind otherwise than through the recognized channels of sense” (Gurney, “Phantasms of the Living”, I, 6); or: “the communication of impressions of any kind from one mind to another independently of the recognized channels of sense” (Myers, “Human Personality”, I, xxi).

The term telepathy is sometimes used, in conformity with its derivation, to mean the direct communication between minds at a great distance. Such terms as thought-transference, mind-reading, or mental suggestion would then apply to the direct communication between minds in the same room or at a small distance. Generally, however, at least in English, telepathy connotes only the exclusion of the recognized channels of sensation, irrespective of the distance.

Intentional communications

Mr. Myers in his “Human Personality and Its Survival of Bodily Death” on the subject of telepathy in its various aspects, obvious and obscure: “Men have in most ages believed, and do still widely believe, in the reality of prayer; that is, in the possibility of telepathic communication between our human minds and minds above our own. Which are supposed not only to understand our wish or aspiration, but to impress or influence us inwardly in return. “So widely spread has been this belief in prayer that it is some- what strange that men should not have more commonly made what seems the natural deduction — namely, that if our spirits can communicate with higher spirits in a way transcending sense, they may also perhaps be able in like manner to communicate with each other. The idea, indeed, has been thrown out at intervals by leading thinkers, from Augustine to Bacon, from Bacon to Goethe, from Goethe to Tennyson. “

Barna research says slightly more than four out of five adults in the U.S. (84%) claim they had prayed in the past week. That has been the case since Barna began tracking the frequency of prayer in 1993. Myers statement that prayer is telepathic communication, means that the majority of the world population Christians, Muslims, Hindus and from many other religions practice telepathic communication.

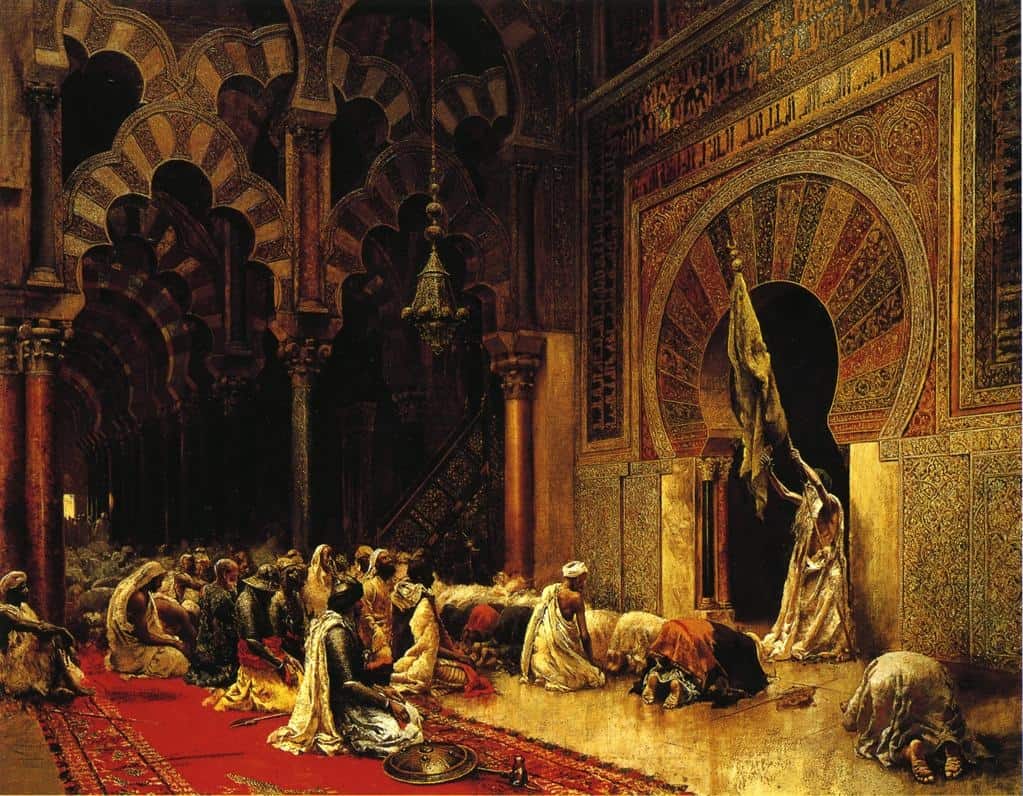

Edwin Lord Weeks (1849 – 1903)

Edwin Lord Weeks (1849 – 1903)

Hulse and Taylor’s 1994 Nobel prize winning work confirmed general relativity to better than a trillionth-of-a-percent precision (1.10 to the 14th). Quantum mechanics has been established with a 1.10 to the 10th precision (Robbert Dijkgraaf). It has been claimed that this makes both theories the best tested theories in existence: Hugh Ross: “Experiments confirm the reliability of general relativity to better than a trillionth of a percent precision. In the words of physicist Roger Penrose, general relativity now ranks as the most rigorously tested and proven theory known to science”.

The meta-analyses that have been applied to Telepathy show an even greater precision:

(Meta-analysis is a quantitative, formal, epidemiological study design used to systematically assess previous research studies to derive conclusions about that body of research. Outcomes from a meta-analysis may include a more precise estimate of an effect).

Dr. Charles T. Tart on meta-analyses, in “The end of materialism”:

“One of the most impressive overviews on precognitive studies I’ve ever seen was an article by parapsychologist Charles (Chuck) Honorton and psychologist Diana Ferrari, published in the Journal of Parapsychology in 1989. They carried out what now become a sophisticated way of assessing bodies of research literature on any phenomenon, a meta-analysis. Such an analysis recognizes that various studies looked at the tagged phenomenon in various ways, under different experimental conditions, and with various degree of experimental rigor and control. When you look at all the published positive and negative results obtained in this way, what’s the best conclusion about the reality or lack of it of the target phenomena? Honorton and Ferrari looked at the all the multiple-choice-type precognition studies published from 1935, when the methods for testing precognition were just evolving, through 1987.

(The studies of precognition in the twenty years since there analysis strengthen and extend their conclusions.)

In the English-language scientific literature they were able to find 309 studies, reported on in 113 articles. Sixty-two different investigators were involved, and the composite database was almost two million trails, generated by more than fifty thousand subjects. Most of the percipients were of course college students.

Many studies involved thoroughly shuffled decks of Zener cards, often with additional randomising factors added after shuffling, such as cutting the deck according the newspaper accounts of the next day’s low temperature in some distant city, while others involved computer-generated target numbers.

The combined results of the studies produced odds against chance of 24 septillion to 1. What is a septillion? It’s 10 with 24 zeros after it, 1024 (1.10 to the 24th ). To put it more simply, it’s preposterous to believe that these cumulated precognitive results were due to chance. Lots of plain guessing was going on, certainly, but every once in a while a genuine precognitive perception of a future state of a targets occurred. One of the common arguments for rejecting evidence for psi phenomena is what’s called the fill-drawer problem.

We humans like success, so a study with positive results is likely to be accepted for publication, and we’ll then know about it, while one with no results probably won’t be accepted.

“Why waste expensive journal space on a study in which nothing happened?” is the way in which an editor might think. Since scientists understand this attitude, they might not even summit the study for publication.

They just leave the results in the file drawer.

A simple way to think about this, is that if you accept the usual 1-to-20 odds against chance as a criterion for “significance,” then if you do experiments in which nothing truth happens, about 1 in 20 of them will show statistical significance by chance alone.

If you get that 1 published and the other 19 languish in your files, a very misleading impression of reality is created.

But suppose you and your colleagues have cumulatively published 10 studies on something, each with a 1-to-20 chance.

If indeed nothing’s really happening that means that there are about 190 unsuccessful studies languishing in various file drawers.

That’s a lot of hidden work! So maybe it’s more likely that something really is happening?

Honorton and Ferrari tested how many unsuccessful, unpublished precognition studies there would need to be to bring the cumulative results of published precognition studies back down to chance results.

They estimated that it would take 14,268 studies to do so. Given that there have never been more than a few people at a time working in experimental psychology, there is no way there could’ve been so many unsuccessful studies been carried out. How about flawed studies? If there is really no precognition than we would expect any apparently successful results to be due to methodological problems like opportunities for sensory cues, improper randomization of targets or recording and analysis errors rated the studies on quality of methodology, and found that not only was it not the case that poorer quality studies were more likely to produce more evidence for precognition, but also they found was that methodologically higher quality studies were associated with better precognition results.

Since Honorton and Ferrari’s meta-analyses, many more studies have shown precognition effects, including unconscious ones. Dean Radin authoritative books (1997, 2006) are excellent places to see these reviewed”.

Dr. Charles T. Tart has been involved with research and theory in the fields of Hypnosis, Psychology, Transpersonal Psychology, Parapsychology, Consciousness and Mindfulness since 1963. He has authored over a dozen books, two of which became widely-used textbooks; he has had more than 250 articles published in professional journals and books, including lead articles in such prestigious scientific journals as Science and Nature.

Dean Radin The Case of Non-Local Perception, a Classical and Bayesian Review of Evidences”: states that it found odds against chance of 12 billion to one.

In 1987, Dean Radin and Nelson did a meta-analysis of all RNG experiments done between 1959 and 1987 and found that they produced odds against chance beyond a trillion to one (Radin 1997: 140).

“From 1974 to 2004 a total of 88 ganzfeld experiments reporting 1008 hits in 3145 trails were conducted. The combine hit rate was 32 % as compared to the chance-expected 25 %. This 7 % above-chance effect is associated with odds against chance of 29.000.000.000.000.000.000 (or 29 quintillion) to 1.

”Dean Radin “Entangled Minds” (120)

“After a century of increasingly sophisticated investigations and more than a thousand controlled studies with combined odds against chance of 10 to the 104th power to 1, there is now strong evidence that psi phenomena exist. While this is an impressive statistic, all it means is that the outcomes of these experiments are definitely not due to coincidence. We’ve considered other common explanations like selective reporting and variations in experimental quality, and while those factors do moderate the overall results, there can be no little doubt that overall something interesting is going on. It seems increasingly likely that as physics continues to redefine our understanding of the fabric of reality, a theoretical outlook for a rational explanation for psi will eventually be established.”

Dean Radin

Source: Entangled Minds: Extrasensory Experiences in a Quantum Reality, Pages: 275

Rather than use my own words to summarise the various types of psi experiment Dean Radin investigated in his book, I have taken the liberty of copying two pages from Chapter 14 of his book, where he does that for us. This outline is simply meant to give a bit more information, and any serious investigator should buy the book, and read it page by page.

Dean Radin The Case of Non-Local Perception, a Classical and Bayesian Review of Evidences”: found odds against chance of 12 billion to one. In 1987, Dean Radin and Nelson did a meta-analysis of all RNG experiments done between 1959 and 1987 and found that they produced odds against chance beyond a trillion to one (Radin 1997: 140). “From 1974 to 2004 a total of 88 ganzfeld experiments reporting 1008 hits in 3145 trails were conducted. The combine hit rate was 32 % as compared to the chance-expected 25 %. This 7 % above-chance effect is associated with odds against chance of 29.000.000.000.000.000.000 (or 29 quintillion) to 1.

”Dean Radin “Entangled Minds”(120) “After a century of increasingly sophisticated investigations and more than a thousand controlled studies with combined odds against chance of 10 to the 104th power to 1, there is now strong evidence that psi phenomena exist. While this is an impressive statistic, all it means is that the outcomes of these experiments are definitely not due to coincidence. We’ve considered other common explanations like selective reporting and variations in experimental quality, and while those factors do moderate the overall results, there can be no little doubt that overall something interesting is going on. It seems increasingly likely that as physics continues to redefine our understanding of the fabric of reality, a theoretical outlook for a rational explanation for psi will eventually be established.”

Dean Radin Source: Entangled Minds: Extrasensory Experiences in a Quantum Reality, Pages: 275

Rather than use my own words to summarise the various types of psi experiment Dean Radin investigated in his book, I have taken the liberty of copying two pages from Chapter 14 of his book, where he does that for us. This outline is simply meant to give a bit more information, and any serious investigator should buy the book, and read it page by page.

Chapter 14.

THE STATE OF THE ARTAfter a century of increasingly sophisticated investigations and more than a thousand controlled studies with combined odds against chance of 10 to the power of 104 to 1 (Table 14-1), there is now strong evidence that some psi phenomena exist.¹ While this is an impressive statistic, all it means is that the outcomes of these experiments are definitely not due to coincidence. We’ve considered other common explanations like selective reporting and variations in experimental quality, and while those factors do moderate the overall results, there can be little doubt that overall something interesting is going on. It seems increasingly likely that as physics continues to refine our understanding of the fabric of reality, a theoretical outlook for a rational explanation for psi will eventually be established.

Table 14-1. A meta-meta-analysis of the classes of experimental evidence considered in this book. The number of studies listed, and the odds against chance, are adjusted for potential selective reporting biases using the trim and fill algorithm. The combined results indicate that these experimental results are unlikely to be due to coincidence or dumb luck. Something else is going on. Genuine psi offers an increasingly plausible interpretation. |

Professor Eysenck, the Psychology Chair at the University of London, and Director of Psychology at the Maudsley and Bethleham Royal Hospitals wrote:

“Unless there is a gigantic conspiracy involving some 30 University departments all over the world and several hundred highly respected scientists in various fields, many of them originally hostile to the claims of the psychical researchers, the only conclusion the unbiased observer can come to must be that there does exist a small number of people who obtain knowledge existing either in other people’s minds, or in the outer world, by means as yet unknown to science.”

Eminent thinkers who took the possibility of telepathy seriously

Nobel Prize-winners:

Henri Bergson (1859-1941), philosopher, 1927 Nobel Prize in Literature, president of the Society for Psychical Research and theoretician of psi.

Barnard, G. W. (2012). Living consciousness: The metaphysical vision of Henri Bergson. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Nicholas Murray Butler (1862-1947), 1931 Nobel Prize in Peace, President of Columbia University, philosopher and diplomat, wrote about psi and helped organize the American Society for Psychical Research.

Butler, N. M. (1886). The Progress of Psychical Research. Popular Science Monthly, 29.

John Eccles (1903-1997), 1963 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, edited a book discussing psi and participated in related conferences.

Eccles, J.C., Mind & Brain.

Albert Einstein (1879-1955), 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics, wrote the preface to a telepathy book (Sinclair, U. Mental Radio.) and commented, ‘We have no right to rule out a priori the possibility of telepathy. For that the foundations of our science are too uncertain and incomplete.’

1946, in Ehrenwald, J. (1978). Einstein skeptical of psi? Postscript to a correspondence. Journal of Parapsychology, 42, p.138.

Brian Josephson (1940-), 1973 Nobel Prize in Physics, has written about psi and been a staunch advocate of psi research for decades.

Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949), 1911 Nobel Prize in Literature, wrote on ostensible psi phenomena.

Maeterlinck, M. (1969) The Great Secret. New Hyde Park, NY: University Books.

Kary Banks Mullis (1944-), 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, has participated in psi research and spoken in support of it.

Radin, D. (2006). Entangled Minds. Extrasensory Perception in a Quantum Reality. New York, NY: Paraview.

Jean Perrin (1870-1942), 1926 Nobel Prize in Physics, was a member of the Institut Général Psychologique’s (IGP) Group of Study of Psychic Phenomena.

Courtier, J. (1908). Rapport sur les séances d’Eusapia Palladino à l’Institut général psychologique en 1905, 1906, 1907 et 1908. Mayenne, France: Impr. de C. Colinnovembre.

Max Planck (1858-1947), 1918 Nobel Prize in Physics and author of quantum theory, expressed his interest in psychical research in his correspondence.

Sully Prudhomme (1839- 1907), 1901 Nobel Prize in Literature, participated in the Société de Psychologie Physiologique’s committee for the study of telepathy.

Collectif (1891). Avis important. Annales des sciences psychiques, 1(2), 73.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852-1934), 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, researched hypnosis and psi phenomena and wrote a book about them (destroyed during the Spanish Civil War).

Sala, J., Cardeña, E., Holgado, M. C., Añez, C., Pérez, P., Periñán, R., & Capafons, A. (2008). The contributions of Ramón y Cajal and other Spanish authors to hypnosis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 56, 361-372.

Charles Richet (1850-1935), 1913 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, founded the Annales des Sciences Psychiques, president of the Society for Psychical Research (1905), and of the Institut Métapsychique International (1923).

Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965), 1925 Nobel Prize in Peace, reported the paranormal phenomena he observed in Africa and remarked that he would like to carry out psi research.

Schweitzer, A. (1951). La Métapsychique au Gabon. Revue Métapsychique, 16, 162-168.

Eugene Wigner (1902-1995), 1963 Nobel Prize in Physics, encouraged research on physics and psi.

Kaiser, D. (2011). How the hippies saved physics. Science, counterculture, and the quantum revival. New York, NY: Norton.

John William Strutt, Lord Rayleigh (1842-1919), 1904 Nobel Prize in Physics, president of the Society for Psychical Research.

Gauld, A., The Founders of Psychical Research.

JJ Thompson (1856-1940), 1906 Nobel Prize in Physics, member of the governing council of the Society for Psychical Research for 34 years.

WB Yeats (1865-1939), 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature, member of the Society for Psychical Research, wrote extensively about psi and esoterism.

Yeats, W. B. (1925/2013). The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats Volume XIII: A Vision: The Original 1925 Version. Scribner.

Other Eminent Figures: Exact Sciences, Engineering, Invention

Olivier Costa de Beauregard (1911-2007), quantum physicist, published on parapsychology, and considered psi phenomena as to ‘be expected as very rational’.

Beauregard, O. C. de (1975). Quantum paradoxes and Aristotle’s twofold information concept. In L. Oteri (Ed.), Quantum physics and parapsychology (pp. 91-108). New York, NY: Parapsychology Foundation.

John Stewart Bell (1928-1990), physicist, developer of the Bell theorem, employee of the European Council for Nuclear Research (CERN), originator of the Bell theorem, wrote about keeping an open mind regarding psi.

Kaiser, D. (2011). How the Hippies Ssaved Physics. Science, counterculture, and the quantum revival. New York, NY: Norton.

David Bohm (1917-1992), quantum theoretician, sought to integrate his theory with psi.

Bohm, D. (1986). A new theory of mind and matter. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 80, 113-135.

Heinrich Hertz (1857-1894), physicist, showed the existence of electromagnetic waves, was a member of the Society for Psychical Research.

Ernst Jordan (1902-1980), quantum physicist, wrote on quantum mechanisms and psi.

Jordan, P. (1951). Reflections on parapsychology, psychoanalysis, and atomic physics. Journal of Parapsychology, 15, 278-281.

Henry Margenau (1901-1997), Higgins Professor of Physics at Yale and staff at Princeton and MIT, philosopher of science, wrote favorably about parapsychology.

Margenau, H. (1970). Principles of evidence in science and their application to parapsychology. In R. Cavanna (Ed.), Psi favorable states of consciousness (pp. 11-17). New York, NY: Parapsychology Foundation.

James Smith ‘Mac’ McDonnell (1899-1980), engineer and chair of the McDonnell-Douglas corporation, supported research in parapsychology.

Thalbourne, M. A. (1995). Science versus showmanship: A history of the Randi hoax. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 89, 344-366.

Edgar Dean Mitchell (1930-2016), aeronautical engineer, 6th person to walk on the moon. He founded the Institute of Noetic Sciences, in which research on psi is conducted, and published a psi study himself.

Mitchell, E. D. (1971). An ESP test from Apollo 14. Journal of Parapsychology, 35, 89-107.

Mathematicians

Burton H Camp (1880-1980), president of the Institute of Mathematical Sciences, wrote that the statistical analyses conducted by Rhine and his team were ‘essentially valid’.

Camp, B. H. (1937). Statement in Notes Section. Journal of Parapsychology, 1, 305.

Alan Turing (1912-1954), mathematician, pioneer of computer science and artificial intelligence, wrote of the ‘overwhelming’ statistical evidence for telepathy.

Turing, A. M. (1950). I. Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind, 59, 433-460.

Psychologists and Social Scientists, Neuroscientists, Biologists, Physicians

Roberto Assagioli (1888-1974), psychiatrist, pioneer of humanistic and transpersonal psychology, wrote a book on psi.

Assagioli, R. (1958). Parapsychological Faculties and Psychological Disturbances. London. UK: Medical Society for Study of Radiesthesia.

Hans Berger (1873-1941), neurologist, created the electroencephalogram, inspired by a telepathic event with his sister.

Berger, H. (1940). Psyche. Jena, Germany: Gustav Fischer.

Sir Alister Hardy (1896-1985), Linacre Professor of Zoology at Oxford, founder of the Religious Experience Research Unit at Oxford, President of the Society for Psychical Research, wrote on psi and religion.

Hardy, A. (1971). Parapsychology in relation to religion. In A. Angoff & B. Shapin (Eds.), A Century of Psychical Research: The continuing doubts and affirmations (pp. 101-110). New York, NY: Parapsychology Foundation.

Sir Julian Huxley (1887-1975), evolutionary biologist and first director of UNESCO, mentioned psi supportively in his writing.

Huxley, J. (1965). Introduction. In P. T. de Chardin The Phenomenon of Man (pp. 11-28). New York, NY: Harper.1985).

CG Jung (1875-1961), founder of analytical psychology, wrote on synchronicity and ostensible psi phenomena.

Jaffé, A. (1967). C. G. Jung and Parapsychology. In J. R. Smythies (Ed.), Science and ESP (pp. 263-280). London, UK: Routledge & K. Paul. (2013).

William Grey Walter (1910-1977), neurophysiologist and robot inventor, wrote on the use of the EEG to investigate psi.

Walter, W. G. (1970). The contingent negative variation and its significance for psi research. In R. Cavanna (Ed.), Psi favorable states of consciousness (pp. 170-188). New York, NY: Parapsychology Foundation

Humanities, Philosophers

Kenneth E Boulding (1910-1993), economist, systems scientist, philosopher, president of the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences, declared to the Washington Star in 1979: ‘The evidence of parapsychology can’t just be dismissed out of hand’.

Anonymous (1990). Newsletter of the ASPR, 16 (2), 19-20.

Rudolf Carnap (1891-1970), philosopher and member of the Vienna Circle, wrote on the importance of researching psi.

Carnap. R. (1963). Intellectual autobiography. In P. Schilpp (Ed.), The philosophy of Rudolf Carnap (pp. 1-84). La Salle, IL: Open Court.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955), philosopher and palentologist, wrote on the evolution of psi abilities.

Chardin, P. T. de (1965). Phenomenon of Man. New York, NY: Harper.

Mircea Eliade (1907-1986), Professor at the University of Chicago, historian of religion and fiction writer, asserted that real paranormal phenomena were at the base of some religious beliefs.

Eliade, M. (2006). Folklore as an instrument of knowledge. In B. Rennie (Ed.), Mircea Eliade: A critical reader (pp. 25-37). London, UK: Equinox (Originally published 1937)

Writers, Artists

Ingmar Bergman (1918-2007), film and theatre director and author, recounted autobiographical ostensible psi phenomena (2005).

André Breton (1896-1966), founder of surrealism and knowledgeable of the psi literature, researched experientially and wrote extensively on psi and automatisms, often in collaboration with other surrealists.

Breton, A. (1928/1964). Nadja. Paris, France: Gallimard/Folio.

Michael Crichton (1942-2008), writer, physician, and filmmaker, wrote about his personal experiences with psi.

Crichton, Michael (1988). Travels. New York, NY: Alfred A Knopf.

Philip K Dick (1928-1982), writer, described various ostensible psi phenomena in his autobiographical works, including xenoglossy and an accurate diagnosis of his son’s hernia.

Carrère, E. (1993/2004). I am alive and you are dead: A journey through the mind of Philip K. Dick. New York, NY: Picador.

Arthur Koestler (1905-1983), author, provided funds for what became the Koestler Unit for the study of parapsychology at the University of Edinburgh, wrote on psi.

Koestler, A. (1972). The Roots of Coincidence. New York, NY: Random House.

Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999), film director, screenwriter, producer, etc., discussed psi positively as an inspiration for his film The Shining.

Show some love

"A philosophical treatise can be mostly written in object or process language,

but phenomenological descriptions must be by its very nature first person descriptions.

It is for this reason that self-observations, and personal experiences of the author are included."

Marinus Jan Marijs.